Newsletter January 11, 2024

What is the State of American Religion in 2024?

It’s only January, but 2024 promises to be an eventful year. For the first newsletter of the year, I want to try something new. I’ve enjoyed sharing new research and data on this newsletter, but there’s more I want to do in this space. There are many other voices I would like to include, people with distinctive perspectives and research backgrounds who are working to expand our understanding of the world. To that end, I’m launching a new feature, American Storylines Voices, a semi-regular Q&A that will feature notable journalists and scholars writing about American politics, culture, and religion. Today I’m excited to share a conversation with Sociologist Claude Fischer, whose work has had a tremendous impact on my own research interests and career.

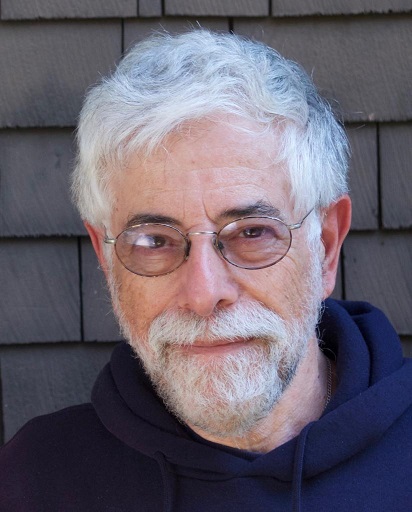

Claude S. Fischer is a Distinguished Professor in the Graduate School in Sociology at the University of California Berkeley. Over five decades, Fischer has written more than I can summarize here spanning a diverse array of topics in social psychology, social history, and religion. He has authored and co-authored numerous academic books, including To Dwell Among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City, America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940, and A Century of Difference: How America Changed in the Last One Hundred Years.

I became familiar with Fischer’s work because of a single journal article: “Why More Americans Have No Religious Preference.” Published more than two decades ago, this article profoundly changed the way many political scientists understood the role of religion in politics and public life. Fischer and his coauthor, Michael Hout, were among the first to document how politics, specifically the rise of the Religious Right, contributed to the rising rates of religious disaffiliation in the United States. My own dissertation exploring the growing religious disaffection of the millennial generation was greatly influenced by this pathbreaking work.

Today, it is widely accepted that political commitments can shape religious beliefs and practices. Donald Trump’s continued strong support among white evangelical Protestants is a testament to this fact. Newly released data from Gallup shows that religious identity is more strongly connected to political identity than ever. Nearly four in ten (38 percent) liberals today are religiously unaffiliated compared to only 11 percent of conservatives. The political division in religious identity has never been wider, and Fischer’s work has never been more relevant.

AS: If you were a scholar at the beginning of your career, what research questions or research topics would you most want to focus on?

CF: That’s a classic sort of question: If I knew then what I know now, I might have invested in Apple stock in 1980. Seriously, however, I have worked in a number of fields—urban studies, personal networks, history of technology, American social history, and a couple of others. The most engaging to me, I feel, has been social history, which perforce includes religious history. My 2010 book, Made in America: A Social History of American Culture and Character, spends a lot of time on religion, both as cultural phenomenon and as social practice.

AS: When it comes specifically to the study of religion, what in your mind are the most important questions that scholars should try to address?

CF: There are, of course, several empirical questions spurred by the “Nones” issue: What are the trends going forward? Who is bailing out and why? What do they say are the reasons and are those the real reasons? What, if anything, are the Nones substituting for organized religion—“spirituality,” more Sunday football, or nothing? How are churches adapting, if they are? Where are there exceptions to this trend? What about cross-national comparisons? And so on.

At a deeper level, I’d like to see a clarification of what we mean by religion. In the west, religion means predominantly the American grassroots Protestantism, with its emphasis on individuals’ personal theologies and on regular congregational prayer as practice. (Thus, survey researchers ask about weekly church attendance but not about, say, giving alms to holy men.) But historically and around the world, religion—or rather, what westerners interpret as religion—is much more varied, including emphases on ritual, vague theologies, ancestor worship, magic, and introspective disciplines. This multiplicity of “religions” may also be connected to our Nones issue; perhaps Americans aren’t abandoning “religion” but are altering their religion.

AS: What do you think people most often get wrong about the changes occurring in American religion?

CF: Since Mike Hout and I started writing about the Nones in 2002, one nagging issue has been the common misinterpretation that people who start refusing to identify with an organized religion were becoming agnostics or atheists. We emphasized the growth of the “unchurched believers” and that what we were detecting was specifically a rejection of standard religious institutions, not of belief. Ironically, twenty years on this misperception has become more accurate, because—and we may have hinted that this might happen; I can’t recall—without the practice of weekly attendance, enrolling children in Sunday school, and the like, it is harder to sustain theological commitments.

More generally, people generally tell a story of religion’s decline as part of the general theme of “decline of community.” And Americans have been declaiming such a decline for centuries, through rises and falls in religious enthusiasm. (A favorite example of mine is President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907 hosting a delegation of ministers asking for his help in stopping an alarming decline in the churches’ “hold on the people.”) This declension theme—everything, particularly the social bond—is falling apart is such a powerful motif in American thought that not much in the way of scholarship can correct it.

AS: How has your own understanding of American religious life evolved since you first wrote the seminal work with Michael Hout documenting the rise of the people with no religious preference?

CF: As background, Mike and I were working on a book project, which became Century of Difference: How America Changed in the Last Hundred Years (2006), in which we trying to collect data on all sorts of social changes. When we started looking at the data on religiosity, we were struck by the then-recent jump in the proportion of survey respondents disclaiming any affiliation. That took us on a detour to write what became our 2002 article. (We learned only later that Normal Glenn had noticed very early signs of this trend in a 1987 paper.)

As to changes in my views, I would point to my earlier comment. I appreciate more that institutions matter and habits matter for belief system. Disengagement, even for people who were only casual adherents to start with, weakens the support for private devotion, private belief, and passing on of tradition. More, while the history of religion in America has its peaks and valleys, there may come a point at which it is all deepening valleys to the horizon.

AS: Scholars such as Robert Bellah have argued that American culture has grown more individualistic while communal life is receding. More recently, Jean Twenge, made the same argument citing technology as precipitating this shift. Jake Meador wrote for the Atlantic suggesting that the decline of religion is connected to rising individualism in American society. How compelling do you find this explanation?

CF: Not much. As I mentioned earlier, the claim that community is dissolving and individualism is running amuck has been a perennial virtually since the Pilgrims landed. It is one of the American myths I challenge in Made in America. (Voluntarism—which blends individualism with active community life so long as it is freely-chosen community—has been long at the core of American culture. The major change has been the expansion of which Americans could participate in this voluntaristic culture, empowering and including Blacks, women, youth, and the working-class over time.) With a few interesting exceptions—see, for instance, Herbert Hoover’s 1922 American Individualism—the chattering classes always see community and personal bonds unraveling from the some golden past.

At times and places, this description may have had some truth. Villages in Puritan New England in the 1700s struggled to maintain unity as families moved out to the countryside and even formed splinter churches or just ignored church. Around 1900, there was legitimate national concern about all the country churches dying in dwindling rural communities and concern as well over the isolation and loneliness about which thousands of farm wives complained. But most often, these never-ending warnings about how we are going off the social cliff (examples: The Lonely Crowd, 1950; A Nation of Strangers, 1972; Bowling Alone, 2000) are rooted in false history and sun-dappled nostalgia.

Maybe someday, as with the boy who cried wolf, one of these alarms will be true. Perhaps today. But for now, color me skeptical.

AS: In 2014, you updated your original research showing that political backlash is an important explanatory factor in the growing number of nonreligious Americans. Nearly a decade later, what else have we learned about fewer people participate in religion in the United States? Is the backlash theory one of the best explanations we have?

CF: Study of the Nones has exploded and, though I keep notes, I haven’t diligently kept up with all of it. I still think that reaction against the political right’s mobilization of the church in the late 20th century is key to explaining why and, importantly, when and for whom disaffiliation surged in the last generation. To be sure, other factors mattered as well. The sexual abuse scandals ranging from the Catholic church to the SBC certainly mattered (although sex scandals are not new). Researchers are doing a good job of assessing exactly who in which church settings and under what conditions exit.