Newsletter July 13, 2023

Turning Against Organized Religion

A few years ago, I made the joke that America is so religious that even our atheists believe in God. At the time, I was commenting on the discrepancy between religious identity and belief. Surveys consistently find that a small but significant number of atheists report that they believe in God.

Early work documenting the beginning of America’s religious decline found that, while people were readily relinquishing their formal affiliations, they retained some spiritual inclinations or religious beliefs. From these early findings emerged new religious categories—the “spiritual, but not religious” and “unattached believers”—to describe groups of indeterminate size and questionable cohesion. Efforts to characterize this important constituency met with limited success. In The Atlantic, Caroline Kircher suggested that they, “reject organized religion but maintain a belief in something larger than themselves. That ‘something’ can range from Jesus to art, music, and poetry. There is often yoga involved.”

This caricature of nonreligious people holds sway in the popular imagination, in large part because of the difficulty identifying shared secular beliefs or experiences. More recent work challenges this view. Still, I think we’ve ignored the most obvious thing that unites nonreligious Americans—their growing disaffection for organized religion. A brand-new poll conducted by the Survey Center on American Life finds that nearly half (47 percent) of religiously unaffiliated Americans believe that the US becoming less religious is a good thing. Less than a decade earlier only 25 percent of unaffiliated Americans expressed this view. Mounting evidence suggests that the nonreligious are shifting from apathy to antagonism and coming to believe that the country might be better off if it had less religion.

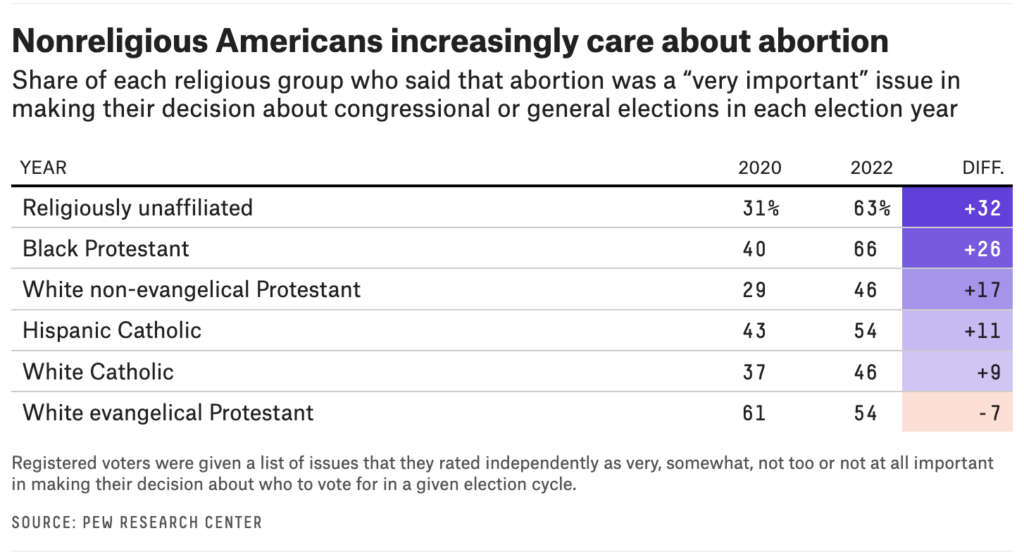

The Battle Over Abortion

A few weeks back, I wrote about some new research with a colleague, Amelia-Thomson Deveaux, about how nonreligious Americans had become strongly committed to preserving abortion access in the wake of the Dobbs decision. We wrote:

Unaffiliated Americans are today overwhelmingly in agreement on abortion — even more so than white evangelicals. A new survey conducted by the Survey Center on American Life found that 60 percent of white evangelical Christians believe that abortion becoming less available is a good thing for society — but a much larger percentage (78 percent) of unaffiliated Americans say this has been a negative development. And a Pew survey found last year that religiously unaffiliated Americans are much more united in support for legal abortion than white evangelicals are in opposition (84 percent vs. 74 percent, respectively). Recent polling also found that 65 percent of nonreligious Americans say the term “pro-choice” describes them very well, a jump from 54 percent roughly a decade earlier.

If nonreligious Americans continue to prioritize support for abortion rights, they are going to face off against conservative Catholics, Mormons, and evangelical Christians. The extent to which secular Americans see religious groups fighting against them on an issue they care about will inform their views about the role of religion in public life more broadly.

Online Christians

Today, a growing share of Americans are raised in homes that have little connection to religion. Most young adults grow up in households that are not engaged in regular religious activity. Even those raised in a religious tradition do not participate as often as previous generations. Increasingly, young people who are not religious have always identified that way. As a result, they have few personal experiences with religious communities and the people in them. Their understanding of the practices and priorities of religious people is drawn from the broader culture rather than personal experiences.

This has important implications for how secular Americans understand the motivations and values of religious people. Without personal participation in a religious community, more nonreligious Americans are exposed to religion in its most divisive and least charitable form—in online arguments over politics.

Negative interactions on social media are incredibly common, but religion researchers are beginning to note that the combative engagement of online Christians can be especially alienating. Sociologist Samuel Perry suggests that the reputational damage self-identified Christians are doing online is considerable.

If our primary interactions are online, or informed by online discourse, then more often than not these interactions will be negative.

Online engagements have left many Americans, including secular people, feeling utterly alienated by the “Christian” approach to politics. One respondent from a recent Pew survey typifies the fundamental change in how Christians are viewed: “‘Christian’ used to be code for polite and decent; now it’s code for the opposite. A ‘Christian nation’ would be intolerant, inflexible and ultimately brutal.”

The Rise of Combative Christianity

Conservative Christians have long felt embattled and belittled by mainstream culture. What is different today is the belief that they are losing. Religious membership continues to decline, traditional families are fading, and American society is undergoing a profound shift in views about gender identity and sexuality. White evangelical Protestants believe Christians are victims of discrimination in American society today.

Feelings of victimhood set the stage for a more combative and cruel type of Christian engagement in politics. In an essay for The Atlantic, Peter Wehner offers an unsparing perspective:

Today, the people in politics who most often invoke the name of Jesus for their political causes tend to be the most merciless and judgmental, the most consumed by rage and fear and vengeance. They hate their enemies, and they seem to want to make more of them. They claim allegiance to the truth and yet they have embraced, even unwittingly, lies. They have inverted biblical ethics in the name of biblical ethics.

With Trump, white evangelical Christians shed an emphasis on personal morality to revel in egregious behavior, so long as it is properly directed at their political foes. Nonreligious people are frequently targets.

It’s not simply a rhetorical shift. The rise of Christian nationalism, which seeks to dominate others by imposing a particular Christian worldview, represents a vision for American civic life that is antithetical to the values of religious pluralism most nonreligious people embrace.

Secular Segregation

Until relatively recently, it was difficult for secular Americans to develop their own network of nonreligious people. But the swelling number of the religiously unaffiliated, combined with their geographic and generational clustering, has led to the development of a new type of religious segregation. In a recent newsletter, I wrote:

A 2020 study found that eight in ten secular Americans have at least one close contact in their life who is also secular, and a majority have two or more. But it's not only friendships; secular Americans are also marrying people whose religious beliefs match their own. A 2021 survey found that more than six in ten (62 percent) secular Americans have a spouse who is also not religious. This represents a profound break from the past.

This matters because religious beliefs, religious behavior, and attitudes about religion have a critical social component. Secular people with many close friends who are religious have far more positive views about the contributions religion makes to American civic and social life than those with few or none.

For a long time, secular identity was assumed to be a temporary experience, a primarily youthful exploration of alternative worldviews or belief systems. We now know that most nonreligious people do not return to the fold as they get older, get married, or have children. A recent Gallup poll found that 75 percent of nonreligious Americans say they are not at all interested in “exploring religion in the future.”

The growing animosity towards organized religion among secular Americans is neither inevitable nor irreversible. It’s unlikely to change unless Christians commit to establishing a positive reputation for their churches and religious institutions, but a growing number of conservative Christians appear uninterested in doing so. Russell Moore, Editor in Chief of Christianity Today, writes in his newsletter: “The kind of cultural Christianity we now see often keeps everything about the Religious Right except the religion. These people aren’t in Sunday school, but they might post Bible verses on Facebook (or quote them on TikTok).” Much of what they’re posting is aimed at taking people down, rather than lifting them up. Too often that’s the most visible face of American Christianity.