Newsletter July 11, 2024

Divorced Men for Trump

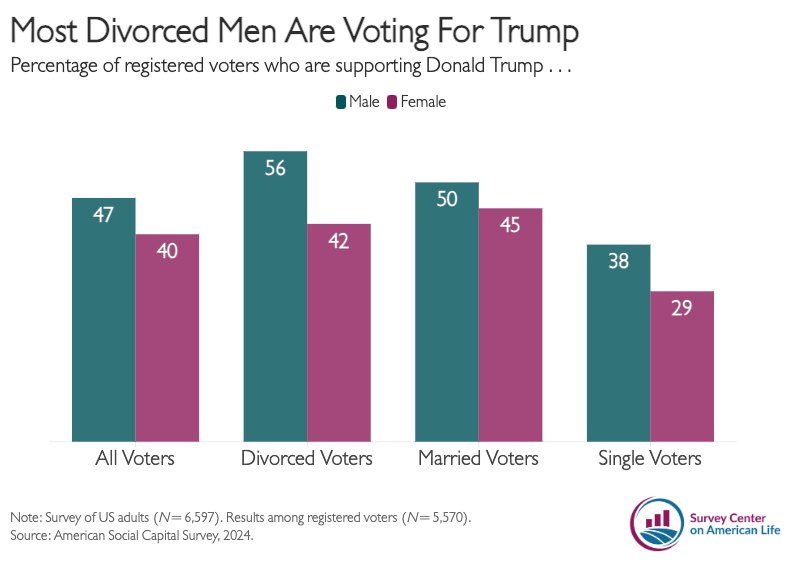

The marriage gap has long been a feature of American politics. Since at least the 1990s, married Americans—both men and women—have voted more consistently for Republican candidates than single Americans have. In 2024, we found that 48 percent of married voters were supporting Trump compared to 34 percent who had never been married, a 14-point gap.

There is another gap that caught my attention recently.

Fifty-six percent of men who are divorced said they are voting for Trump, compared to 42 percent of divorced women. The voting divide between men and women is larger among the formerly married than any other group. Married men and women report supporting Trump at remarkably similar rates (50 percent vs. 45 percent). Single men are somewhat more likely to vote for Trump than single women, a statistic that has been a topic of considerable comment.

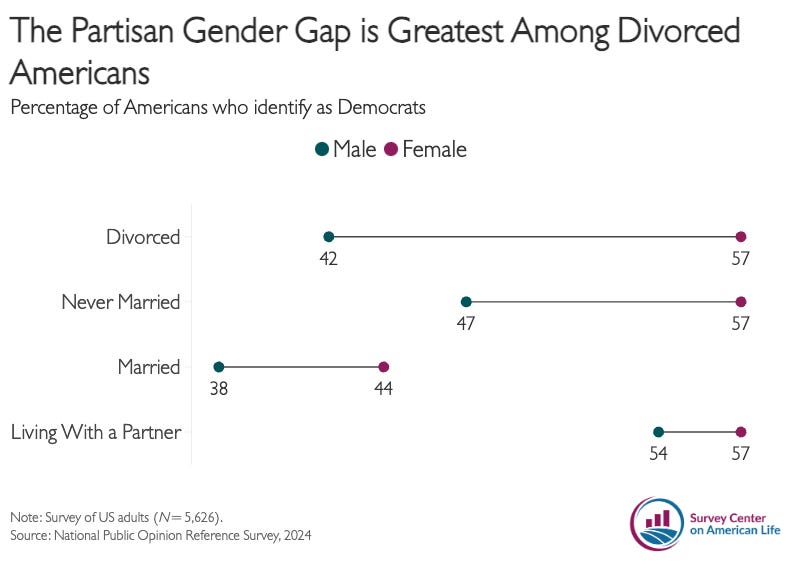

The divorce divide in American politics is something new. Or rather, it’s something that’s rarely discussed. It’s not limited to voting preferences either. Divorced women are far more Democratic than divorced men, and the gender gap is wider among this group than any other. A majority (57 percent) of women who are currently divorced, and not remarried, identify as Democrats, compared to only 42 percent of divorced and not remarried men. The gender gap among married Americans is less than half the size, and even smaller among cohabitating couples. There’s a notable partisan gap among never-married Americans—women are significantly more Democratic than men (57 percent vs. 47 percent), but it’s still not as large as the gap among Americans who are divorced.

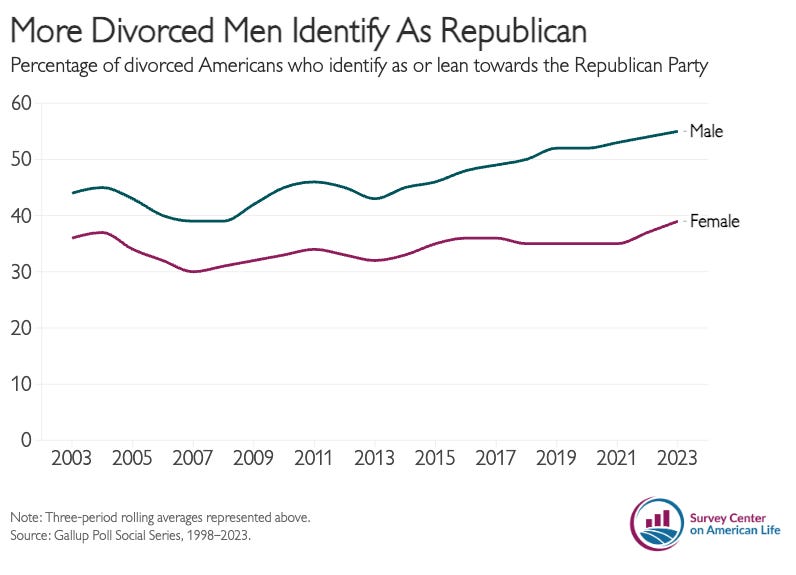

What to make of this? First, it’s unlikely that it’s simply a quirk in the data since the pattern emerges from multiple high-quality sources. It also appears to have been around for a while. Looking back over the past two decades reveals an enduring division. However, in the last decade, the gender gap in political identity among this group has grown. Gallup polls show that the political divide between divorced men and women is larger today than it has been at any time over the last 20 years. A majority (54 percent) of divorced men identify as Republican compared to 41 percent of divorced women.

That married couples are politically aligned is not terribly surprising. Research has shown that couples “tend towards like-mindedness” in their political outlook over the span of the marriage. It’s even less so for Americans in cohabitating relationships. Political identity has become a salient factor in romantic partner selection, especially with the rise of online dating, and in the US cohabitating couples tend to be comparatively young. One research paper found that politics played a significant role in the evaluation of prospective partners online, and their willingness to communicate. The authors write: “We find that participants consistently evaluate profiles more positively (e.g., had a greater interest in dating the individual presented) when the target’s profile shared their political ideology.”

The explanation for the expanding political gap among formerly married Americans is less clear-cut. I do not believe that political differences are directly contributing to the dissolution of marriages. Research typically finds that domestic violence, infidelity, conflict, and an overall lack of commitment are the most cited precipitating factors. There is some evidence that politically heterogeneous couples have lower levels of relationship satisfaction. But these couples are still largely satisfied with their marriages. A more compelling explanation is that having different values and views about traditional gender roles and domestic responsibilities creates conflict that can end a marriage.1

Part of what I think is happening is that as Americans spend more time uncoupled, they are more likely to develop a tribal approach to politics, a tendency to see the political interests of men and women as fundamentally at odds. The rising sense of anxiety felt by men and women about their place and future in America makes it more difficult to appreciate the problems of others. What’s more, these feelings of insecurity and grievance are being channeled through our politics.

Shortly after his felony conviction, the New York Times reported that Donald Trump attended an Ultimate Fighting Championship event in Newark, New Jersey. It was a raucous affair with more than 16,000 in attendance. The New York Times reports:

“The crowd was diverse in every way — ethnicity, age, nationality — except gender. It was almost entirely male. Fathers and sons. Men on their own. Men in suits. Men in shorts. The precious few women attending appeared to be on dates.”

More than any time in the recent past, American politics is pushing men and women apart rather than bringing them together. Too often candidates speak explicitly to the individual interests of men and women, rather than offering a single shared vision.

Today, men and women are less connected and committed to each other. We desperately need to cultivate opportunities for men and women to see each other, understand each other, become invested in their troubles, and celebrate their triumphs. I always cringe when I hear men say they care about a particular issue women are facing because “I have a wife, daughter, etc.” and not because it’s an experience roughly half of the population shares.

Politics did not create the current gender rift, but it is making things worse. Men and women who have ever been hurt or mistreated by the opposite sex more readily make their pain public, and their personal grievances become politicized. The consequences will not be pretty.

1 I should point out that any relationship category is not permanent. In our surveys, respondents who are currently divorced may stay that way permanently or get remarried in the future. Men are more likely to get remarried than women, but it’s difficult to predict in what way it would matter. The remarriage rate is also declining rapidly. Most Americans who get divorced remain that way.

Read more on American Storylines