Newsletter November 7, 2024

2024 Election Edition: Young Men Swing Toward Trump

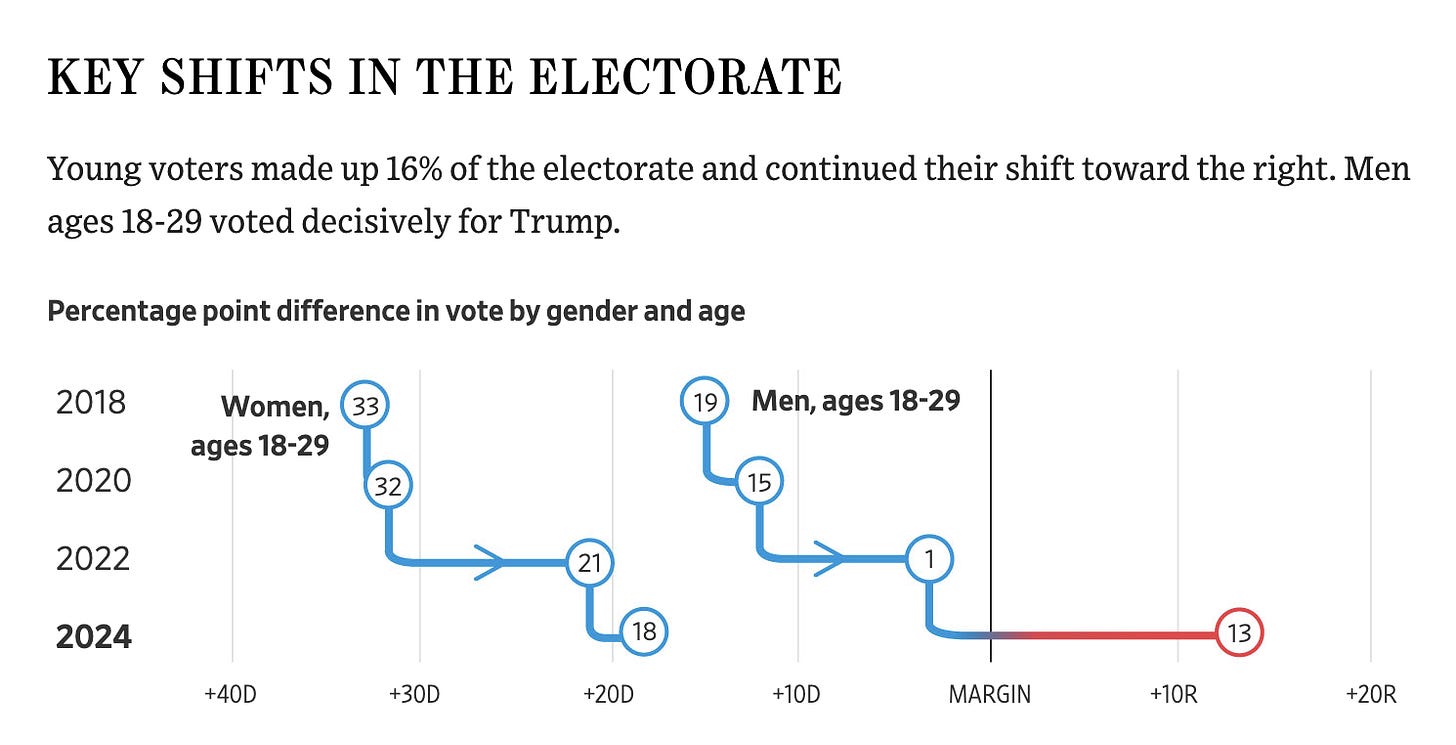

Roughly 10 months ago I wrote a piece titled: “Will Young Men Vote For Trump?” in which I speculated whether young voters would undergo a political decoupling in 2024. Now post-election polls confirm that is precisely what happened. Fifty-six percent of young men voted for Trump in the 2024 election according to the Associated Press’ VoteCast poll. Only 40 percent of young women voted for Trump, a 16-point gender gap.

For the last two years, I’ve been writing about the critical fissure that is opening up between young men and women. Not only in politics, but in their social attitudes and personal experiences as well. But the political divide is stark. This past Tuesday, Trump received more support from young men than any Republican candidate in more than two decades.

Looking back over the past few elections, the Wall Street Journal found that the gender gap among young Americans expanded significantly this year, increasing from 17 points in 2020 to 31 points in 2024.

For those ready to argue that young men supported Trump because did not like the idea of voting for a woman, the VoteCast data offers a simpler explanation: Most young men like Donald Trump. Fifty-five percent of young men who voted in the 2024 election said they had a favorable view of Trump.

What Mattered in 2024?

The 2024 election outcome defies a single, simple explanation—Trump improved among a diverse range of voters, both demographically and geographically. The most parsimonious explanation for Trump’s surprisingly strong performance is the decline in social capital—Trump has benefitted immensely from the rising levels of distrust among the public.

Over the last two decades, a remarkable civic divide emerged separating Americans with college degrees from everyone else. College graduates have more friends, a more extensive network of people they can rely on for financial and social support, are more connected to social and civic organizations, and subsequently live more stable, comfortable lives. As noncollege Americans witnessed the steady deterioration of their social and economic foundations, they lost faith in critical institutions.

More than differences in style, temperament or tone, the most distinguishing characteristic between Harris and Trump in the eyes of many voters was this: One candidate asked voters to trust the current political and economic order, the other candidate promised to dismantle it.

There were signs if you knew where to look. A New York Times/Siena poll conducted shortly before the election found that “nearly half of all voters said they were skeptical that the American experiment in self-governance was working, with 45 percent saying that the nation’s democracy does not do a good job representing ordinary people.” The same poll found that more than six in ten voters agreed that “the government is mostly working to benefit itself and elites.”

Voters who lost faith with the existing political and economic order swung to Trump in large numbers. Harris gained among wealthy and college-educated voters; Trump gained with everyone else. Americans living in border towns, cities and suburbs lost confidence in the government to curb illegal immigration, reduce crime, and lower prices. Trump won all these voters—those who said crime, inflation and immigration were the most important issues.

The deficit in trust is not the only advantage that Trump had. Incumbent parties are struggling across the globe. Gallup’s polling strongly suggested that any Democratic candidate would have an uphill climb this year. But the lack of confidence so many Americans have in their economic and political institutions is critical to understanding Trump’s victory.

Further Reading:

New York Times Columnist David Brooks makes a similar argument: “Voters to Elites: Do You See Me Now?”

“Society worked as a vast segregation system, elevating the academically gifted above everybody else. Before long, the diploma divide became the most important chasm in American life. High school graduates die nine years sooner than college-educated people. They die of opioid overdoses at six times the rate. They marry less and divorce more and are more likely to have a child out of wedlock. They are more likely to be obese. A recent American Enterprise Institute study found that 24 percent of people who graduated from high school at most have no close friends. They are less likely than college grads to visit public spaces or join community groups and sports leagues. They don’t speak in the right social justice jargon or hold the sort of luxury beliefs that are markers of public virtue.”

Read more on American Storylines