January 5, 2023

Faith After the Pandemic: How COVID-19 Changed American Religion

Findings from the 2022 American Religious Benchmark Survey

The COVID-19 pandemic touched nearly every aspect of American life. Schools, offices, grocery stores, and churches faced daunting challenges in the early days of the pandemic in their efforts to operate while keeping their employees, members, and the broader community safe. For churches and religious organizations, concerns over COVID-19 led many to pause traditional in-person worship services. A recent Pew Research Center study found that nearly one in three churches or religious organizations were completely closed in summer 2020, while others moved outside or online. By March 2022, most were offering some type of regular service, but only 43 percent of religious Americans reported that services currently being offered by their place of worship were back to their pre-pandemic operations.[1]

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted religious participation for millions of Americans. In summer 2020, only 13 percent of Americans reported attending in-person worship services. This rebounded to 27 percent by March 2022, but rates of worship attendance were still lower than they were before the pandemic.[2] However, the pandemic did not appear to affect one’s faith, with most adults reporting that their religious affiliation today was no different than it was pre-pandemic. In fact, one study showed that the experience of the pandemic may have even strengthened many Americans’ religious faith.[3]

To better understand how COVID-19 and church closures influenced patterns of religious attendance and identity, the Survey Center on American Life at AEI teamed up with researchers at NORC at the University of Chicago to measure religious affiliation and attendance both before the pandemic (2018 to March 2020) and again in spring 2022. For the 2022 American Religious Benchmark Survey, interviews were conducted with the same people to enable us to measure actual changes in religious behavior or identity. These data give us a unique opportunity to understand what changes, if any, the pandemic had on America’s religiosity.

The results show that religious identity remained stable through the pandemic. White mainline Christians and white evangelical Christians were the two largest religious groups both pre-pandemic and in spring 2022. Unaffiliated adults also made up a quarter (25 percent) of adults in both periods. Nineteen percent of adults changed their religious identification during the pandemic, including 6 percent who were unaffiliated pre-pandemic but reported a religion in spring 2022 and 5 percent who reported a religion pre-pandemic but then were unaffiliated in spring 2022.

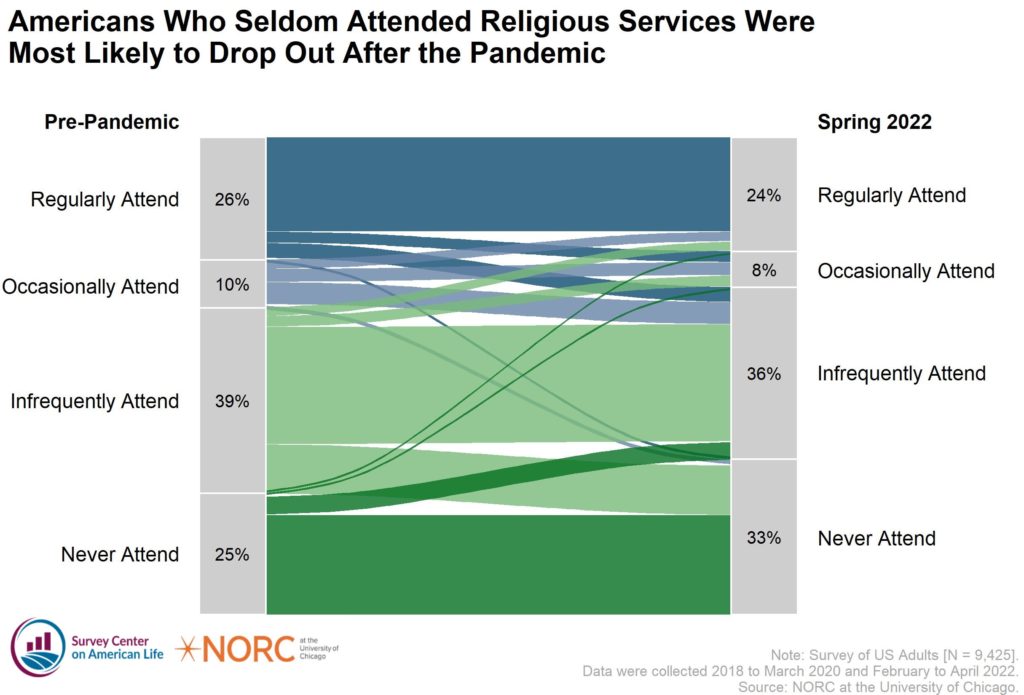

However, religious attendance was significantly lower in spring 2022 than it was pre-pandemic. In spring 2022, 33 percent of Americans reported that they never attend religious services, compared to one in four (25 percent) who reported this before the pandemic. There was less change among the most religiously engaged Americans. Before the pandemic, 26 percent of Americans reported attending religious services at least once a week, similar to the 24 percent who did so in spring 2022.

The survey also reveals who remained at the pews, who returned to the pews, and who left. Conservatives, adults age 50 and older, women, married adults, and those with a college degree were more likely to attend than were other groups in both periods.

Most adults continued to attend at the same rate as pre-pandemic, including adults age 65 and older, adults with a college degree or higher, and Mormon adults, white evangelical Christians, and white Catholics. Adults age 30–49, adults with less than a college degree, and black Protestants saw the largest increases in attendance between the two periods. Twice as many adults decreased attendance than increased attendance, however. Adults under age 50, adults with a college degree or less, Hispanic Catholics, black Protestants, and white mainline Protestants saw the largest declines in attendance.

Religious Change and Measurement

In 2021, the General Social Survey (GSS) documented a significant increase in the number of Americans identifying as religiously unaffiliated. The GSS found that 29 percent of Americans were unaffiliated in 2021, compared to 23 percent in 2018.[4] However, Landon Schnabel, Sean Bock, and Mike Hout have shown that survey administration may have contributed to the observed changes.[5] The authors find that some religious respondents are increasingly less likely to respond to online surveys.

To address this concern, the 2022 American Religious Benchmark Survey reinterviewed the same respondents, using the same modes of interviewing (online and over the phone) for both periods. These data allow us to isolate the degree of change. Additionally, the AmeriSpeak panel members included in this survey were initially recruited using multiple modes such as online, telephone, and in-person interviewing, which is intended to recruit a more representative sample and mitigate potential nonresponse biases arising in online-only surveys.

Religious Identity Remains Consistent Through the Pandemic

Nationally, religious identity among American adults has stayed largely consistent during the pandemic, with minimal evidence of religious switching during this period. The religious composition of the public in the years before the pandemic and after are nearly identical. Before the pandemic, 17 percent of American adults were white mainline Protestant; 14 percent were white evangelical Protestants. White Catholics comprised one in 10 Americans before the pandemic. Nine percent of Americans were black Protestants. Another 6 percent of Americans identified as Hispanic Catholic. Members of the Church of Latter-day Saints made up 2 percent of the public, and 1 percent of Americans were Jewish. One in four Americans (25 percent) claimed no religious affiliation—or were religiously unaffiliated. These remained essentially unchanged in spring 2022, with religious groups nearly identically sized before and after the pandemic.

While the national distribution of religious affiliations stayed consistent, there was some movement at the individual level. Nineteen percent of individuals changed their religious affiliation between pre-pandemic and spring 2022, including 6 percent who were unaffiliated pre-pandemic but reported belonging to a religious tradition in spring 2022. A similar number (5 percent) identified with a religious tradition pre-pandemic but then were unaffiliated in spring 2022.

Religious Service Attendance Declined After the Pandemic

While religious identities remained stable, the pandemic took a toll on religious attendance. After the pandemic, more Americans reported that they never attend religious services or attend less frequently than they did in the years before.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, 75 percent of Americans reported attending religious services at least once a year, including about one-quarter (26 percent) who attended regularly (at least a few times a month). By spring 2022, roughly two-thirds of the public reported attending religious services at least once a year.

Much of this decline in attendance was due to people completely abstaining from worship. The number of Americans who became completely disconnected from a place of worship increased significantly over the past few years. Before the pandemic, one in four Americans reported that they never attended religious services. By spring 2022, that share increased to 33 percent.

Who Left and Who Stayed?

The pandemic does not appear to have affected religious attendance equally. Certain demographic groups were more likely than others to report lower levels of worship attendance in spring 2022.

Conservatives, older Americans, married adults, and college-educated Americans reported less of a decline in regular worship attendance than other Americans did. In fact, their frequency of attendance at religious services was largely similar before and after the pandemic. In contrast, young adults (age 18 to 29), liberals and moderates, and Americans without a college degree were all more likely to never attend religious services before and after the pandemic.

Conservatives were more likely to attend religious services, and especially to do so regularly, than liberals and moderates were. In spring 2022, 20 percent of conservatives never attended service. That was a 6 percentage point increase from the 14 percent who never attended before the pandemic. Liberals saw an even steeper increase from 31 percent never attending pre-pandemic to 46 percent in spring 2022. Those changes result in a 26 percentage point gap between liberals and conservatives attending at all.

The age gap in religious attendance widened during the pandemic. Pre-pandemic, three in 10 (30 percent) young adults and 20 percent of seniors (age 65 or older) said they never attended religious services, a 9 percentage point gap. In spring 2022, more than four in 10 (43 percent) young adults said they never attended services, compared to 23 percent of seniors. There was almost no change in the proportion of seniors who regularly or occasionally attend services.

Women were more likely than men to attend religious services before the pandemic, and this remains true today. However, both saw a decline in religious attendance over this period. The percentage of women never attending religious services increased 8 percentage points, from 23 to 31 percent. The percentage of men never attending religious services experienced a similar increase in nonattendance, rising from 28 to 34 percent.

Married adults were more likely than adults who have never married to attend religious services both pre-pandemic and in spring 2022. Both groups also saw an increase in the percentage reporting they never attended services in spring 2022. However, adults who have never married saw a much larger increase in the percentage never attending than married adults did. Those who have never married saw a 14 percentage point increase, compared to a 6 percentage point increase for married adults.

Adults with a college degree or higher were more likely to attend religious services both pre-pandemic and in spring 2022. The percentage of adults never attending religious services increased in all education groups.

Changes in frequency of attendance also differed across religious traditions. Mormons, white evangelical Christians, and Jews showed relatively little change in their attendance patterns. Other religious traditions demonstrated a modest decline in religious attendance. The percentage of white mainline Protestants who report never attending services increased from 17 percent to 24 percent. White Catholics and Hispanic Catholics also experienced a notable uptick in those who never attend (11 percent to 18 percent and 10 percent to 20 percent, respectively). Even religiously unaffiliated Americans who reported low levels of religious participation before the pandemic are even less likely to attend today. Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of religiously unaffiliated Americans say they never attend services now, compared to 62 percent before the pandemic.

Patterns of Attendance Were Stable for Most Americans

Despite the significant increase in Americans who never attend religious services, most Americans report attending at rates similar to before the pandemic. Most adults attended religious services pre-pandemic and in spring 2022 at the same frequency when looking at changes in religious attendance at the individual level. Two-thirds (68 percent) of adults reported the same frequency of attendance pre-pandemic and in spring 2022. However, the pandemic appears to have resulted in an overall depression of religious participation. Among the remaining third, twice as many adults reported attending religious services less or much less often, compared to 11 percent of adults who reported an increase in attendance.

The increase in Americans who report never attending religious services was largely driven by those who had sporadic attendance patterns before the pandemic. Nearly all Americans who have shifted to no longer attending religious services at all were those who infrequently attended before the pandemic. Few Americans who were regularly attending before the pandemic report that they no longer attend at all. And few of those who were occasionally attending services before the pandemic report that they do not attend anymore.

Were Young Adults Uniquely Affected?

No group of Americans has undergone more significant change in religious attendance than young adults. More than four in 10 young adults report different levels of religious participation today than they did before the pandemic. Only 58 percent of young adults report the same level of religious attendance in spring 2022 as they did a couple years earlier. Nearly one in three (30 percent) young adults are attending religious services less often today, while 12 percent are more active. In contrast, three-quarters of seniors are attending just as often today as they were before the pandemic. Sixteen percent of seniors are attending less often than they were before, and 9 percent are more involved.

There were also notable differences among religious groups. Hispanic Catholics and black Protestants saw significant decreases in attendance compared to Mormons and white evangelical Christians. Eight in 10 Mormons report no change in their frequency of worship attendance from before the pandemic to spring 2022. More than seven in 10 white evangelical Christians (73 percent), white Catholics (71 percent), and the religiously unaffiliated (72 percent) also changed their rates of worship attendance. In contrast, roughly six in 10 black Protestants (61 percent) and Hispanic Catholics (61 percent) report the same level of religious attendance.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted much of American society, including religious worship. Rather than completely upending established patterns, the pandemic accelerated ongoing trends in religious change. Young people, those who are single, and self-identified liberals ceased attending religious services at all at much higher rates than other Americans did. Even before the pandemic, these groups were experiencing the most dramatic declines in religious membership, practice, and identity. At least in terms of religious attendance, the pandemic appears to have pushed out those who had maintained the weakest commitments to regular attendance.

The decline of religious attendance and the stability of religious identity over the past two years suggest a decoupling of identity and experience. Increasingly, religious affiliation may tell us less about the full range of religious and spiritual experiences Americans have and the extent of their theological commitments. Past research has shown that Americans who regularly attend services are more likely to embrace the formal tenets of their faith and share similar cultural worldview as their coreligionists. Nearly every major religious tradition—with just two exceptions—has experienced a drop in worship attendance. This gap may also signal the rise of cultural religiosity—with identity linked to ethnic or cultural aspects of the tradition rather than specific religious beliefs or rituals.

Finally, the post-pandemic religious decline may portend increasing religious polarization, with more Americans either very religiously active or completely inactive. The surveys reveal little change among those who regularly attend. Very few Americans who were most active in their places of worship before the pandemic have since left. However, those who were attending infrequently—attending just a few times a year—dropped at a much higher rate.

Before the pandemic, roughly half of Americans were occasionally or infrequently attending services. Now, that number has dropped to about four in 10. Conversely, the percentage of Americans who never attend or attend at least weekly has increased. These changes in worship help us understand how the pandemic has diminished—perhaps permanently—the role of religious participation in the lives of individual Americans and society as a whole.

Acknowledgements

The NORC team would like to acknowledge the help of researchers Semilla Stripp and Michelle Whitlock on this project.

About the Authors

Lindsey Witt-Swanson is a Research Director in the Public Affairs and Media Research Department at NORC at the University of Chicago.

Jennifer Benz is vice president of Public Affairs and Media Research at NORC at the University of Chicago and deputy director of The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

Daniel A. Cox is a senior fellow in polling and public opinion at the American Enterprise Institute and the director of the Survey Center on American Life.

Methodology

NORC conducted the 2022 American Religious Benchmark Survey on behalf of, and with funding from, the American Enterprise Institute. The purpose of this study was to create high-quality benchmark and trend data on key religion measures of the US adult population.

This study used AmeriSpeak, NORC’s probability-based panel designed to be representative of the US household population. During the initial recruitment phase of the panel, randomly selected US households were sampled with a known, nonzero probability of selection from the NORC National Sample Frame and then contacted by US mail, email, telephone, and field interviewers (face-to-face). The panel provides sample coverage of approximately 97 percent of the US household population. Those excluded from the sample include people with only PO Box addresses, some addresses not listed in the US Postal Service Delivery Sequence File, and some newly constructed dwellings.

The pre-COVID-19 pandemic data include responses to the following two questions provided by panelists between 2018 and March 2020:

- What is your present religion, if any?

- Protestant (for example, Baptist, Methodist, nondenominational, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Pentecostal, Episcopalian, or Reformed Church)

- Roman Catholic (Catholic)

- Mormon (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or LDS)

- Orthodox (Greek, Russian, or some other orthodox church)

- Jewish (Judaism)

- Muslim (Islam)

- Buddhist

- Hindu

- Atheist (do not believe in God)

- Agnostic (not sure if there is a God)

- Nothing in particular

- Just Christian

- Unitarian (Universalist)

- Something else

- How often do you attend religious services?

- Never

- Less than once per year

- About once or twice a year

- Several times a year

- About once a month

- Two to three times a month

- Nearly every week

- Every week

- Several times a week

A sample of these panelists were asked these questions again as part of AmeriSpeak’s Core Adult Profile Refresh collected from February 3, 2022, to April 4, 2022. Respondents had the option of completing via phone or web in English or Spanish. Respondents were offered a small monetary incentive for completing the survey. In total, the data include 9,425 panel members with religiosity data before the pandemic and who responded to the refresh survey in 2022. Because the data were collected through various panel surveys, no cases were removed due to quality issues.

The overall margin of a sampling error is plus or minus 1.4 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level, including the design effect. A sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error, and there may be other unmeasured errors in this

Weights were developed for all panel respondents to account for their probability of selection into the sample of panel recruits, panel recruitment nonresponse adjustments, and post-stratification adjustments of the recruited panel to match population benchmarks. An additional adjustment was made to account for the study design. The weighting benchmarks were obtained from the most recent Current Population Survey at each time point.

Data and Analyses

The six demographic variables of interest were recoded to overcome categories with small n sizes and to allow for easier interpretation of the analyses. The religion variable was also recoded to overcome small n sizes and incorporate race. The analyses primarily included the use of frequency distributions and t-tests to test significance between time points and demographic groups.

About NORC at the University of Chicago

NORC at the University of Chicago is an independent research institution that delivers reliable data and rigorous analysis to guide crucial programmatic, business, and policy decisions. Since 1941, NORC has conducted groundbreaking studies, created and applied innovative methods and tools, and advanced principles of scientific integrity and collaboration. Today, government, corporate, and nonprofit clients around the world partner with NORC to transform increasingly complex information into useful knowledge.

NORC conducts research in five main areas: economics, markets, and the workforce; education, training, and learning; global development; health and well-being; and society, media, and public affairs.

For more information, email info@norc.org.

Notes

[1] Justin Nortey, “More Houses of Worship Are Returning to Normal Operations, but In-Person Attendance Is Unchanged Since Fall,” Pew Research Center, March 22, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/03/22/more-houses-of-worship-are-returning-to-normal-operations-but-in-person-attendance-is-unchanged-since-fall.

[2] Nortey, “More Houses of Worship Are Returning to Normal Operations, but In-Person Attendance Is Unchanged Since Fall.”

[3] Neha Sahgal and Aidan Connaughton, “More Americans Than People in Other Advanced Economies Say COVID-19 Has Strengthened Religious Faith,” Pew Research Center, January 27, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/01/27/more-americans-than-people-in-other-advanced-economies-say-covid-19-has-strengthened-religious-faith.

[4] General Social Survey, website, https://gss.norc.org.

[5] Landon Schnabel, Sean Bock, and Mike Hout, “Switch to Web-Based Surveys During Covid-19 Pandemic Left Out the Most Religious, Creating a False Impression of Rapid Religious Decline,” SocArXiv, October 16, 2022, https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/g3cnx. [1] A change-in-religious-attendance variable was created to model changes in religious attendance between the two periods. An individual’s reported religious attendance (regularly, occasionally, infrequently, or never) pre-pandemic was subtracted from spring 2022, resulting in values from negative three to three measuring both directional change and magnitude. Zero change was coded as “same,” changes of one more or less were coded as “more” and “less,” and changes of two or three more or less were coded as “much more” and “much less.” An ordered logistic regression was used to model religious attendance.