Blog November 7, 2022

The Class Divide in Family Dinner

The family dinner was once a ubiquitous feature of American life, an experience shared across cultural, religious, and class lines, but it has disappeared in many households. Far fewer Americans report having regular meals with their family during their formative years. Baby Boomers were far more likely to have grown up having meals with their families than Millennials and Gen Zers. Only 38 percent of Gen Zers who are now adults report that their family ate together regularly growing up.

The disappearance of family dinner is not simply a function of generational changes in values and priorities. Increasingly, family dinners reflect the growing class divide in American society. In Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, Robert Putnam documents how the class divide in family dinners emerged during the 1990s and has expanded since. Today, college educated Americans are far more likely than those without a college education to have been raised in homes where family dinners were the norm. This wasn’t always the case.

Older Americans, regardless of educational background, report having eaten dinner as a family regularly during childhood. Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of Americans age 50 or older without any college education report that they had family meals every day during childhood, roughly as many (79 percent) Americans that age with a post-graduate education who say the same.

For younger Americans, the story is entirely different. Among Americans under the age of 50, education now strongly predicts whether one had regular family meals growing up. Only 38 percent of younger Americans without a college education were raised in homes that shared meals every day. In contrast, more than six in ten (61 percent) younger Americans with a post-graduate education say their family ate together regularly.

The Family Dinner Decline

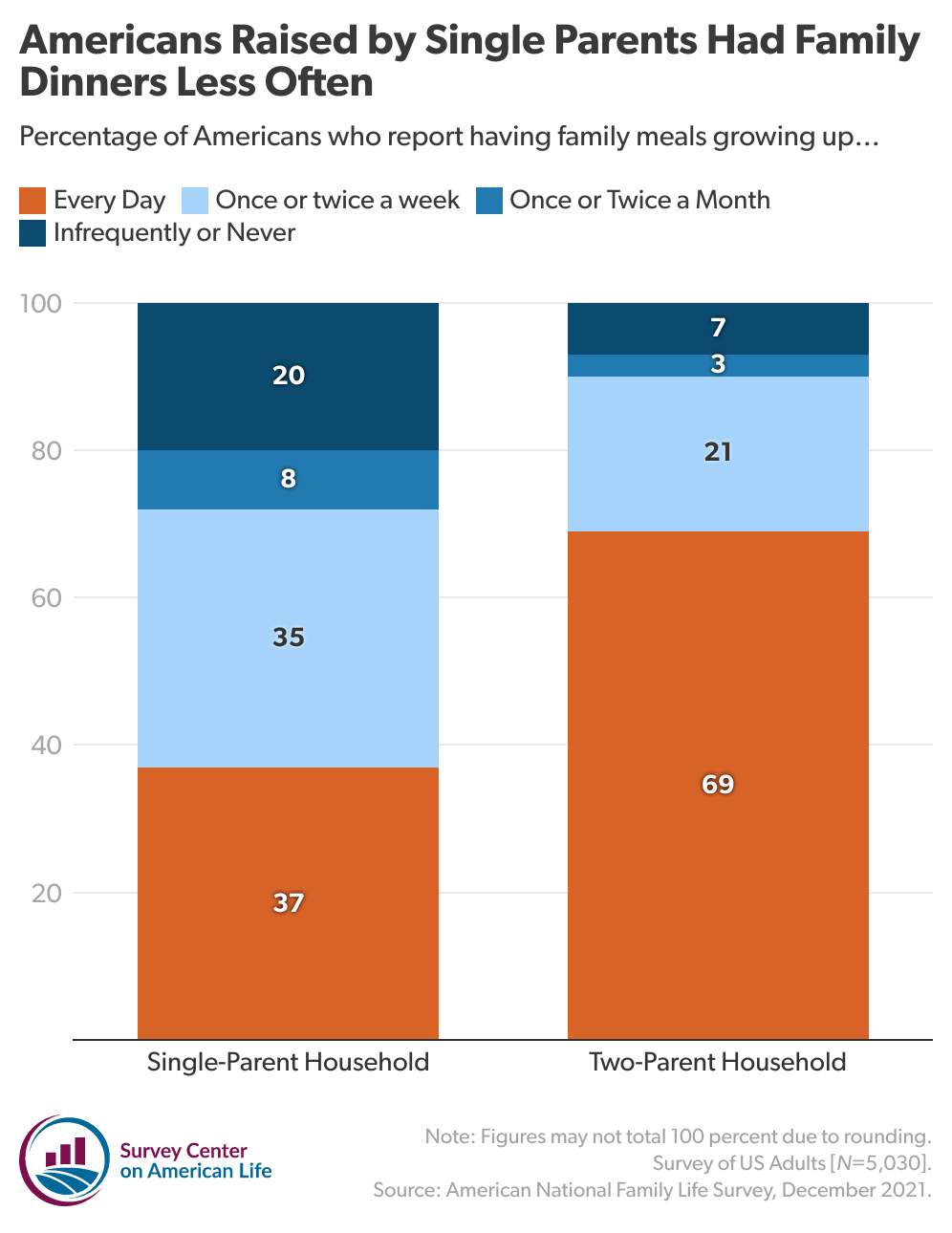

There are a variety of explanations for the family dinner decline. Evolving parental priorities are certainly one. But it’s also a reflection of how some of our most basic and essential formative experiences have become stratified along class lines. Compared to a generation ago, Americans without a college education are far more likely to raise children outside of marriage, and Americans raised in single-parent households are much less likely to report having regular family meals.

In Our Kids, Robert Putnam describes the challenges many single parents face, capturing the difficult tradeoffs harried parents are often forced to make. Reflecting on a conversation with Stephanie, a single mother with four children, and her daughter Lauren, Putnam notes how Stephanie balances competing demands on her time:

As a hardworking single mother, Stephanie struggles to cope with demands on her time and energy and this has affected her style of parenting in many ways. "Parent-child conversations over dinner, for example, were uncommon. We're not a sit-down-and-eat family," Stephanie says. "We didn't do that. You got to the table, you ate." "When it’s time to eat," Lauren adds "it's whoever wants to eat. It wasn't everybody sit at the table, like a party or something." "We ain't got time for all that talk-about-our-day stuff," Stephanie explains.

Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis

In Stephanie’s household, family mealtimes were informal and infrequent.

Why Family Meals Matter

An extensive body of research documents the multiplicity of benefits provided by regular family meals. First, family meals provide parents the opportunity to model appropriate behavior, communicate values, and establish and reinforce cultural traditions. Jane Waldfogel has shown that, “Youths who ate dinner with their parents at least five times a week did better across a range of outcomes: they were less likely to smoke, to drink, to have used marijuana, to have been in a serious fight, to have had sex . . . or to have been suspended from school.” Research has also shown family mealtimes spur intellectual development among children by providing opportunities for them to acquire vocabulary and general knowledge. Studies have even shown that kids who eat family meals regularly tend to have better diets and to develop healthier eating habits later in life. Finally, my own research has shown that the experience of having regular meals is strongly associated with positive relationships among family members.

The decline of family meal time represents a significant loss for children, but it is not a burden that is being shared equally across society. Working class families are now far less likely to share meals together. It’s not the most important example of the growing inequality between Americans with college educations and those without. However, as Putnam argues, “it is one indicator of the subtle but powerful investments that parents make in their kids (or fail to make).”